A Death in Harlem by Karla F.C. Holloway. In 1920s Harlem, in the middle of an awards ceremony for Black artists, one of the winners, a beautiful young woman (Black, but light-skinned enough that she could have passed for white, if she'd chosen to) falls out of a window to her death. Did she jump? Was it an accident? Or was she... murdered?!?! Weldon Thomas, the city's first Black policeman, is on the case.

The problem quickly turns out to be not a lack of motive, but too many motives. Almost everyone seems to have a potential reason to kill Olivia: the prominent doctor she was rumored to be having an affair with; the doctor's wife who was seen fighting with Olivia earlier in the day; the wife's best friend (and former lover) who was angry at being spurned when Olivia came on the scene; the white art collector who was present at the awards ceremony but mysteriously disappeared immediately afterwards; Olivia's maid who knew too much; Olivia's former maid who left her for a better job; the wife's maid who is determined to protect her employer; the mayor's son, who was drunk and in Harlem that night; and on and on. Every single character has at least one dangerous secret.

I love stories set during the Harlem Renaissance and I love murder mysteries, so I was very excited for A Death in Harlem. Unfortunately this is Holloway's first time writing fiction, and it really shows. The characters all feel one-dimensional, none of them get an arc or chance to deepen, there's too much switching between different POVs, and much of the dialogue feels stiff and unrealistic. Whenever there's a bad guy, Holloway practically has them twisting their mustaches and cackling evilly as they praise their own villainous deeds. Which... I'm sure plenty of white people in 1920s NYC were horrible racists! But here they come off less as examples of historical accuracy and more like signs around the bad guys' necks so that the audience knows who to boo.

On another note, Olivia's life and death are paralleled with that of a poor, dark-skinned sex worker; they both arrive in NYC on the same day and later die on the same day, but while Olivia is formally mourned and her case investigated, the other woman's death passes unnoticed. This is a nice conceit, but the other woman essentially disappears from the book after the first few chapters, and her plot is never drawn into the main story. I get what Holloway was trying to say with this, but I don't think it worked.

I would read another book by Holloway, because I liked many of her choices and think she has potential, but this one was a bit meh.

I read this as an ARC via NetGalley.

In light of the trashfire that has been the Romance Writers Association over the last few weeks (a brief summary for anyone who hasn't been following this story), I decided that it was an excellent time to catch up with Courtney Milan, who I have loved for a long time but whose most recent books I hadn't yet read.

After the Wedding by Courtney Milan. A historical romance set in 1860s England, the second full-length novel in The Worth Saga (there are also three novellas in the series). Lady Camilla Worth was once the daughter of an earl. But as a young girl her father was convicted of treason and committed suicide, and Camilla went to live with a distant relative. When he got bored of raising a 12 year old, he passed her on to a yet more distant relative, who did the same, and again, and again, each time reducing her status a little more. By age twenty she's working as a common servant for a village rector, who constantly threatens her with hell because she once had premarital sex. She has no way of contacting her remaining family and won't even try, completely convinced that they want nothing to do with her.

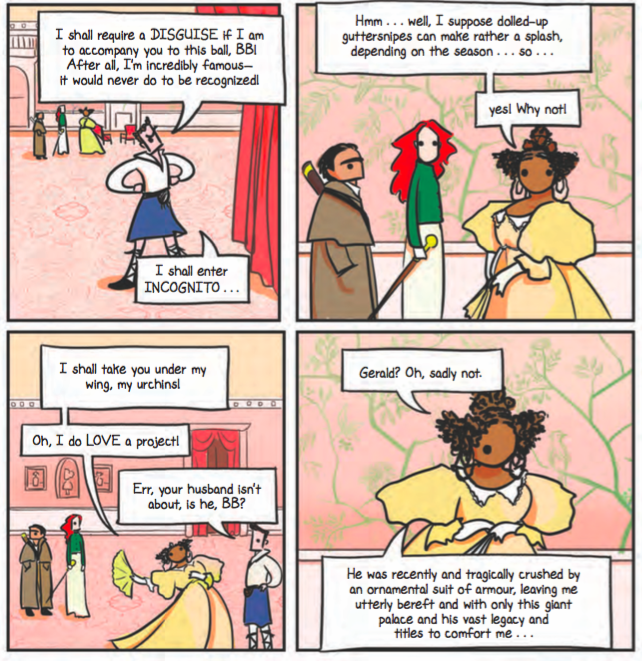

Adrian Hunter is the son of an extremely successful Black businessman and a white abolitionist. Now he's a wealthy and competent businessman himself (supervising a porcelain factory, which was a cool historical detail), but he really wants to prove to his brother that their uncle, a white bishop, is worth trusting. The bishop says he'll publicly recognize the Black side of his family if Adrian just does him one favor... go undercover as a valet to spy on the bishop's ecclesiastical rival. In short order Camilla and Adrian are servants in the same household, caught alone in a room together, and forced into a (literal shotgun) marriage. Adrian knows that if they want a successful annulment, they can't sleep together or otherwise appear to be married, which leads to a lot of EXTREMELY IDDY pining as they slowly fall in love and yet can't touch or even talk about it.

So, yes, it is a historical romance with many of my favorite tropes: fake marriage, angst, searching for family, lots of humor, finding inspiration through reading dusty court records (okay, this isn't a trope I've previously encountered but I loved it), and, of course, sooooo much glorious pining. I also adored many of the side characters, particularly Adrian's brother, who was amazing and who I was extremely excited to discover is slated to be the hero of the next book in the series.

On the negative side, After the Wedding had much less to do with the Opium Wars/treason/bigger plot of the Worth Saga than Once upon a Marquess did, which was a disappointment to me because that's definitely the part of the series I'm most interested in. After the Wedding is a bit of a shallower book. On the hand, I devoured the whole thing in only two days and had a great time while reading, so I can't complain too much.

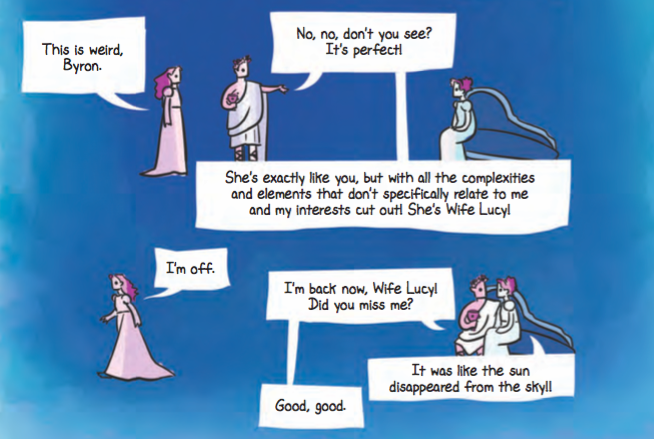

Mrs Martin’s Incomparable Adventures by Courtney Milan. The third novella in The Worth Saga (this comes immediately subsequent to After the Wedding, but they're so disconnected from one another that it doesn't really matter). Mrs Bertrice Martin is a 73 year old widow, immensely rich, with nothing much to bother her except that her Terrible Nephew keeps trying to steal her money and rape her servants. (Which, I mean, is quite the problem.) Also she's lonely and everyone in her life keeps treating her like she's stupid and fragile. Violetta Beauchamps is a 69 year old boarding house manager, the latest victim of Terrible Nephew's habit of running up debts that he doesn't intend to pay. As a result of his actions, she's out of a job and out of a home. She plans to con Bertrice into giving her enough money to retire on, but quickly gets caught up in Beatrice's plans to ruin Terrible Nephew's life. Along the way, they fall in love.

As much as I adore the idea of elderly lesbian seductions, Mrs Martin’s Incomparable Adventures works better as a screwball comedy than as a romance. The various mishaps they subject the Terrible Nephew to (geese, offkey renditions of the hallelujah chorus, paying all the neighborhood's sex workers to avoid him) are unrealistically over-the-top but frequently hilarious. Bertrice's unflappable confidence leads to some fabulous dialogue: "Oh, for God's sake. Forty-nine is extremely young. If forty-nine is not young, that would make me old, and I am not old. I have reached the age of maturity to which all humans must particularly aspire; to dismiss this pinnacle of perfection as old age is to demean all of humankind."

It's also a book in which the phrase "men are horrible" is repeated approximately once per page, so if you're in the mood for that, it's extremely the book you want. And aren't we all in the mood for that sometimes? The author's notes say that Milan wrote this in the shadow of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, which... yeah, it definitely feels like a book for that moment. I could have asked for a bit more sexual tension between the main characters, but eh, it works great as a comedy if not as a serious love story. Another light, fast read.

Also there is cheese toast. No one can dislike a book that praises cheese toast.

The problem quickly turns out to be not a lack of motive, but too many motives. Almost everyone seems to have a potential reason to kill Olivia: the prominent doctor she was rumored to be having an affair with; the doctor's wife who was seen fighting with Olivia earlier in the day; the wife's best friend (and former lover) who was angry at being spurned when Olivia came on the scene; the white art collector who was present at the awards ceremony but mysteriously disappeared immediately afterwards; Olivia's maid who knew too much; Olivia's former maid who left her for a better job; the wife's maid who is determined to protect her employer; the mayor's son, who was drunk and in Harlem that night; and on and on. Every single character has at least one dangerous secret.

I love stories set during the Harlem Renaissance and I love murder mysteries, so I was very excited for A Death in Harlem. Unfortunately this is Holloway's first time writing fiction, and it really shows. The characters all feel one-dimensional, none of them get an arc or chance to deepen, there's too much switching between different POVs, and much of the dialogue feels stiff and unrealistic. Whenever there's a bad guy, Holloway practically has them twisting their mustaches and cackling evilly as they praise their own villainous deeds. Which... I'm sure plenty of white people in 1920s NYC were horrible racists! But here they come off less as examples of historical accuracy and more like signs around the bad guys' necks so that the audience knows who to boo.

On another note, Olivia's life and death are paralleled with that of a poor, dark-skinned sex worker; they both arrive in NYC on the same day and later die on the same day, but while Olivia is formally mourned and her case investigated, the other woman's death passes unnoticed. This is a nice conceit, but the other woman essentially disappears from the book after the first few chapters, and her plot is never drawn into the main story. I get what Holloway was trying to say with this, but I don't think it worked.

I would read another book by Holloway, because I liked many of her choices and think she has potential, but this one was a bit meh.

I read this as an ARC via NetGalley.

In light of the trashfire that has been the Romance Writers Association over the last few weeks (a brief summary for anyone who hasn't been following this story), I decided that it was an excellent time to catch up with Courtney Milan, who I have loved for a long time but whose most recent books I hadn't yet read.

After the Wedding by Courtney Milan. A historical romance set in 1860s England, the second full-length novel in The Worth Saga (there are also three novellas in the series). Lady Camilla Worth was once the daughter of an earl. But as a young girl her father was convicted of treason and committed suicide, and Camilla went to live with a distant relative. When he got bored of raising a 12 year old, he passed her on to a yet more distant relative, who did the same, and again, and again, each time reducing her status a little more. By age twenty she's working as a common servant for a village rector, who constantly threatens her with hell because she once had premarital sex. She has no way of contacting her remaining family and won't even try, completely convinced that they want nothing to do with her.

Adrian Hunter is the son of an extremely successful Black businessman and a white abolitionist. Now he's a wealthy and competent businessman himself (supervising a porcelain factory, which was a cool historical detail), but he really wants to prove to his brother that their uncle, a white bishop, is worth trusting. The bishop says he'll publicly recognize the Black side of his family if Adrian just does him one favor... go undercover as a valet to spy on the bishop's ecclesiastical rival. In short order Camilla and Adrian are servants in the same household, caught alone in a room together, and forced into a (literal shotgun) marriage. Adrian knows that if they want a successful annulment, they can't sleep together or otherwise appear to be married, which leads to a lot of EXTREMELY IDDY pining as they slowly fall in love and yet can't touch or even talk about it.

So, yes, it is a historical romance with many of my favorite tropes: fake marriage, angst, searching for family, lots of humor, finding inspiration through reading dusty court records (okay, this isn't a trope I've previously encountered but I loved it), and, of course, sooooo much glorious pining. I also adored many of the side characters, particularly Adrian's brother, who was amazing and who I was extremely excited to discover is slated to be the hero of the next book in the series.

On the negative side, After the Wedding had much less to do with the Opium Wars/treason/bigger plot of the Worth Saga than Once upon a Marquess did, which was a disappointment to me because that's definitely the part of the series I'm most interested in. After the Wedding is a bit of a shallower book. On the hand, I devoured the whole thing in only two days and had a great time while reading, so I can't complain too much.

Mrs Martin’s Incomparable Adventures by Courtney Milan. The third novella in The Worth Saga (this comes immediately subsequent to After the Wedding, but they're so disconnected from one another that it doesn't really matter). Mrs Bertrice Martin is a 73 year old widow, immensely rich, with nothing much to bother her except that her Terrible Nephew keeps trying to steal her money and rape her servants. (Which, I mean, is quite the problem.) Also she's lonely and everyone in her life keeps treating her like she's stupid and fragile. Violetta Beauchamps is a 69 year old boarding house manager, the latest victim of Terrible Nephew's habit of running up debts that he doesn't intend to pay. As a result of his actions, she's out of a job and out of a home. She plans to con Bertrice into giving her enough money to retire on, but quickly gets caught up in Beatrice's plans to ruin Terrible Nephew's life. Along the way, they fall in love.

As much as I adore the idea of elderly lesbian seductions, Mrs Martin’s Incomparable Adventures works better as a screwball comedy than as a romance. The various mishaps they subject the Terrible Nephew to (geese, offkey renditions of the hallelujah chorus, paying all the neighborhood's sex workers to avoid him) are unrealistically over-the-top but frequently hilarious. Bertrice's unflappable confidence leads to some fabulous dialogue: "Oh, for God's sake. Forty-nine is extremely young. If forty-nine is not young, that would make me old, and I am not old. I have reached the age of maturity to which all humans must particularly aspire; to dismiss this pinnacle of perfection as old age is to demean all of humankind."

It's also a book in which the phrase "men are horrible" is repeated approximately once per page, so if you're in the mood for that, it's extremely the book you want. And aren't we all in the mood for that sometimes? The author's notes say that Milan wrote this in the shadow of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, which... yeah, it definitely feels like a book for that moment. I could have asked for a bit more sexual tension between the main characters, but eh, it works great as a comedy if not as a serious love story. Another light, fast read.

Also there is cheese toast. No one can dislike a book that praises cheese toast.